07 February 2010

Follow the frankincense trail

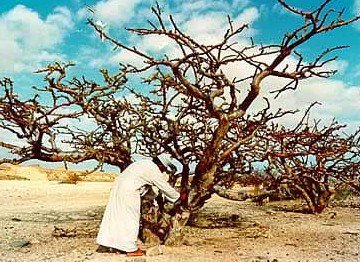

With deft strokes, a Bedouin chips away the grey, papery bark, then smoothes a green patch the size of your hand on the tree; it’s a scrubby, scraggly and unpretentious tree. As if by magic, milky white tears of gum-resin start welling up in the freshly made green wound.

The Bedouin moves to another tree continuing his harvest. At some of the trees, the Bedouin man finds trees that he has recently tapped and from these he removes handfuls of precious sap that has now hardened to a golden hue – this is frankincense, one of the world’s most precious substances that is now so rarely used in the developed world.

The trees that the Bedouin would have tapped are Boswellia sacra and we were in an imaginary walk through the fabled frankincense groves of Oman’s desert plateau that borders the green mountains of Dhofar. This is where the best frankincense is grown as this is where the ideal conditions are – a steady tropical sun, pale limestone soil and an heavy dew from the monsoon.

Omani frankincense has a subtle aroma of balsam that recalls distant shrines or northern pine forests. The trade in frankincense struggles like many of the ancient spice and ingredients trades as they are hard work for the money that you can make – in the Middle East, young men would rather work in the oil fields rather than the frankincense fields, while in Sri Lanka, young men would rather work in a bank than learn to prepare cinnamon bark.

From these chunks of golden resin, a whole economy flourished along the frankincense trail, from ancient Arabia to distant Greece and Rome. On the back of the camel, this river of incense built up fabled kingdoms with names that have a haunting romantic quality and litter the texts of the Bible – Main, Hadramawt, Nabataea, Saba (of the fabled Queen of Sheba) and Qataban.

These ancient city states had their own languages, their own histories, their own law and religions, their own art and architecture and they created dams and irrigation to develop agriculture to feed their peoples and water systems to provide pure, luscious water for their people. Then their kingdoms collapsed before slipping into the dust of ancient history, becoming forgotten tales and monuments (like at Petra) for tourists to gawp at.

The Egyptians used the “perfume of the gods” for temple rites and as a base for perfumes; frankincense is first recorded on the tomb of Queen Hatshepsut from the 15th century BC, where it says that she had sent an expedition to the land of Punt (perhaps in Somalia) to go and get some frankincense. In 450BC, Herodotus, the Greek Father of History, mentioned the aromatics of Arabia – “The whole country is scented with them and exhales an odour marvellously sweet.” In the Roman world, incense perfumed cremation rites and Nero lavished a whole year’s production of frankincense on the funeral of his consort, Poppaea.

The trade in frankincense nowadays is obscure and a very small niche, but in 100 – 200AD, Southern Arabia sent over 3,000 tons every year along the frankincense trail to Greece and Rome.

This 2400 mile trail began in Hadramawt in South Yemen around the ancient of Sabota. Pliny the Elder wrote “Frankincense...is conveyed to Sabota on camels…The Kings have made it a capital offence for camels so laden to turn aside from the high road”. The camels would have collected the frankincense from the valley of Wadi Hadramawt with its cities, Shibam, Sayun and Tarim. From Sabota, the camel trains would go to Qana for shipment overseas and trading with India for spices or north to Timna and then through Saba, the ancient kingdom of Sheba. After Marib, they would travel to Main and then to Mecca, al Medina and finally to Petra, where the ancient Nabatean Kingdom traded incense and spices with the Roman Empire.

Was it from one or more of these ancient frankincense kingdoms, that the magi brought their wisdom and their gifts worthy of a prince. Along the trail, the caravans would collect myrrh, salt and indigo. For the Magi, frankincense symbolised divinity, an offering equal in importance to gold and myrrh.

Today, the best frankincense comes from Oman, with Hadramawt long gone as the centre of the trade. Frankincense is also grown in India, Somalia and the Yemen.