20 February 2023

The Mystery Of The Lost Kingdom of Rheged

Reading Taliesin's Heroic Poems unlocked a new way of seeing the space around here. Through them, I have come up with a possible landscape for the Old North, Rheged and the realm where Urien lived in the sixth and seventh centuries.

I have just finished reading a book called ‘Lost Realms’ by Thomas Williams. In it, he has a chapter on Rheged, where he essentially plays down the whole idea of Rheged arguing that it is likely fantasy – Urien is seen as an unlikable character and that ‘it is necessary to accept that Rheged may be no more than an imaginative projection onto a blank region of space and time, an illusion to satisfy the tastes and political aspirations of later generations of Welsh princes – no more real than [Geoffrey of Monmouth’s] land of Gorre.’ Although Thomas Williams does concede that ‘the idea that a real British kingdom of Rheged lies behind the poems remains an inherently plausible one.’

For me, the issue is that nobody really seems to believe that the places in Taliesin’s poems exist in a sensible location, nor that there is a workable chronology.

However, I really do believe that they exist and that there is a workable timeline. Basically, I think I may have worked out where the poems of Taliesin are located, as well as those of Aneirin. It is quite a short story so I perhaps can explain. After reading ‘The Battle of the Trees’, I put the book to the side, but then after a few weeks I began reading it again.

So, as in all good plans, I skipped the introduction and started at poem 1. That was okay, then I went to poem 2 and I immediately knew exactly where I was. When I read the third poem, I was certain. And when I read through all the early legendary poems, they were in the same place and the landscape opened up to me – except for a few poems which must be located in different places and time. It was all very sudden, quite unexpected and a bit weird to be honest.

I then went back to read the introduction and soon realized no one else thought the same way, but (as I read more around the subject) I realized I was only half crazy and that my landscape was perhaps a possible explanation for the poems. Indeed, I think the geography was a key element for the poems, essentially being to preserve the shape and battles of a lost kingdom for the Rhegedian diaspora in Gwynedd.

The key is that, unbeknownst to me, I seem to live in Erechwydd and almost every day I look towards Llech Wen and Rheged. I never knew it until a few weeks ago, but the more I look at the details the more likely it seems. Indeed, the more I read around it the more everything slots into place.

The poem ‘The Men of Catraeth’ opens:

‘The men of Catraeth are up with the sun

Around their commander, the triumphant cattle-thief.

It’s Urien himself, the far-famed chieftain,

Who holds kings in check and cuts them down.

Misfortune for the men of Prydyn’s armies!

Gwen Ystrad’s a fort fit for warrior’s struggle’

Then, later, we have:

‘In the struggle for Gwen Ystrad, a man might see

Trouble closing in, champions tired out with killing.

Going down to the ford, I saw bloodstained men

Laying their sword’s at the grey-haired king’s feet.’

And:

‘The Lord of Rheged, I marvel at his daring.

I saw great heroes gather round Urien

When he slaughtered his enemies at Llech Wen’

The start of my discourse is fairly standard, even if it is denied by many. Basically, Catraeth (or Aneirin’s Gatreath) is Catterick. Gwen Ystrad is Wensleydale not the alternative, Winsterdale, because you need to think of it geographically as going down from the North York Moors-Cleveland Hills rather than as most picture it coming from Cumbria over the Dales to Yorkshire – that is the main first point, the conventional narrative has Cumbria at the centre and stretches to Catterick, whereas I am saying Catterick is more central and we need to travel the other way around. I think this is because Cumbria and Cymry have the same linguistic root, so the normal idea is that the Old North goes from Wales up through Cumbria and into Dumfries and Galloway, towards Strathclyde then over to Edinburgh. For me, the Old North is a much smaller and narrower place that will become more obvious as I go through my thoughts. In fact, Wales went from Gwynedd through Elmet into Rheged and Gododdin, so a different route altogether.

An alternative understanding of Catraeth is that it breaks down as ‘Cat’ ‘Traeth’ so is ‘Battle-Sound or Sand’, so is not an identifiable place but a description for an unspecified battlefield. Perhaps, though, we can reconcile this as a word play between ‘Catterick’ the place and the battlefield.

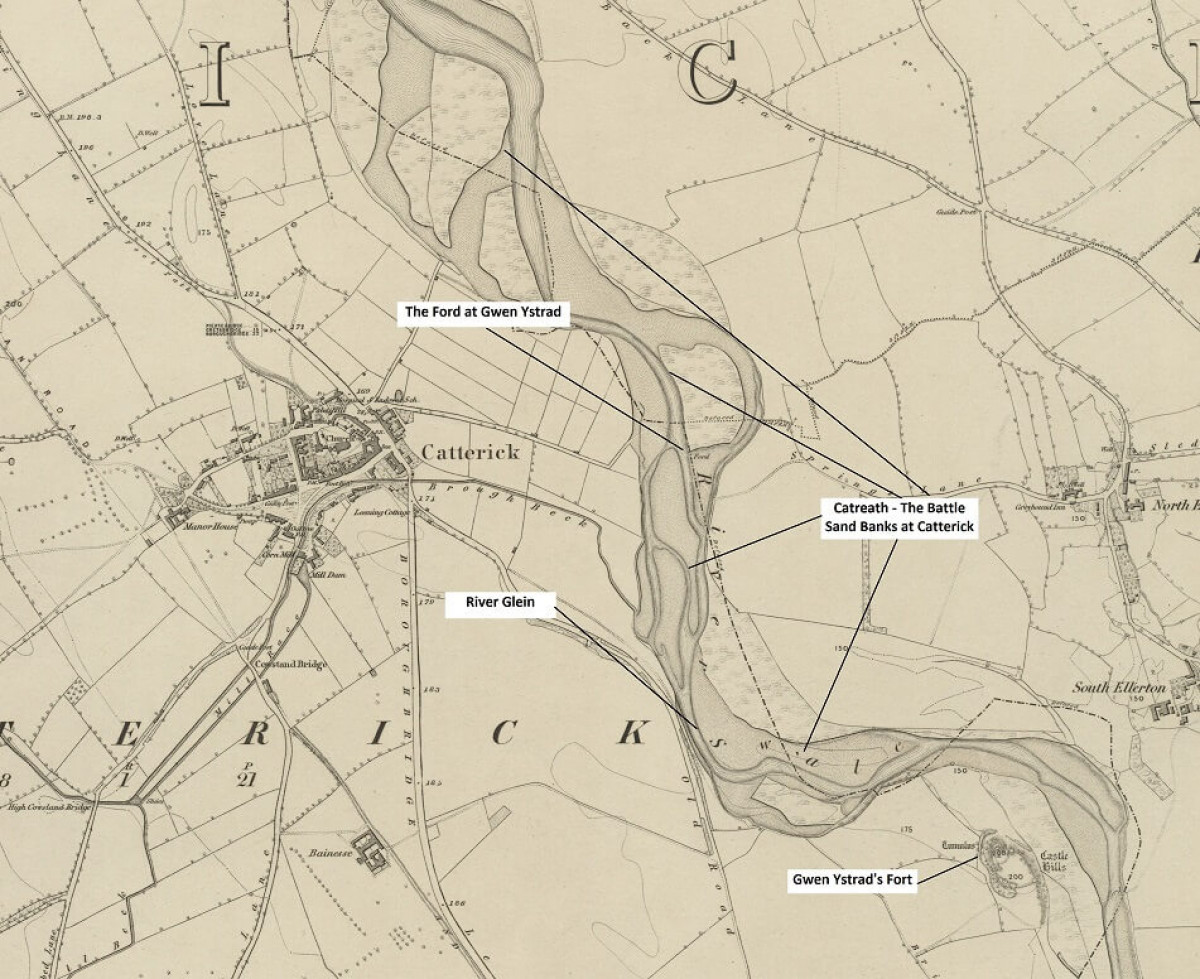

Anyway, I decided to look at the old maps. Frighteningly, the Swale just below the castle at Catterick is one whole bunch of sand banks. There is a large sandy, embanked area on the Swale just below the fortress, so this really could be the site of the battle. The battle of Catterick and Wensleydale (Catreath and Gwen Ystrad) may, therefore, have been fought here at the river’s edge. There is even a ‘ford’ clearly marked, so my take is that the battle of Catterick was fought below the fort of Gwen Ystrad near the river Swale against the ‘sandbanks’ and that Urien took the surrender of the defeated attackers by the ford. It is not unknown for water and rivers to be used as a battle tactic, for example Threave Castle near Castle Douglas is on an island; the Black Douglases knew a safe route to ride their horses over the river Dee to their stronghold, so they were able to evade any pursuers.

Next, Llech Wen may be what it translates as, ‘The White Stone’ or Whitestone Cliff, which is beside Thirsk. It is sometimes called White Mare Crag because of a local myth. So, nearby, we have Sutton-under-Whitestonecliffe. Whether this is the Llech Wen or it was another hill nearby is by-the-by, but the hillside glistens white and on a good day I can look towards the White Horse that was carved out in the hillside during the Victorian times – this is actually made by covering the ground with white limestone chips so like many good things is a fake.

This is why it is Gwen Ystrad or Wensleydale, because the North York Moors-Cleveland Hills are on a limestone plateau, whereas the Pennines are not, so the whiteness goes from east to west, not west to east. However, perhaps the fort at Catterick is, also, known as Gwen Ystrad and Llech Wen. Whatever the detailed solution, it does seem plausible that Gwen Ystrad and Llech Wen are in Wensleydale, whether it is the valley itself, the area around Catterick or above Thirsk, and any changes between these places does not change the overall concept?

That is all a quite standard analysis.

Now, for the different things. Where is Erechwydd, Rheged and Llwyfenydd?

‘Urien of Erechwydd’ begins with the lines:

‘Urien of Erechwydd,

Most generous Christian.’

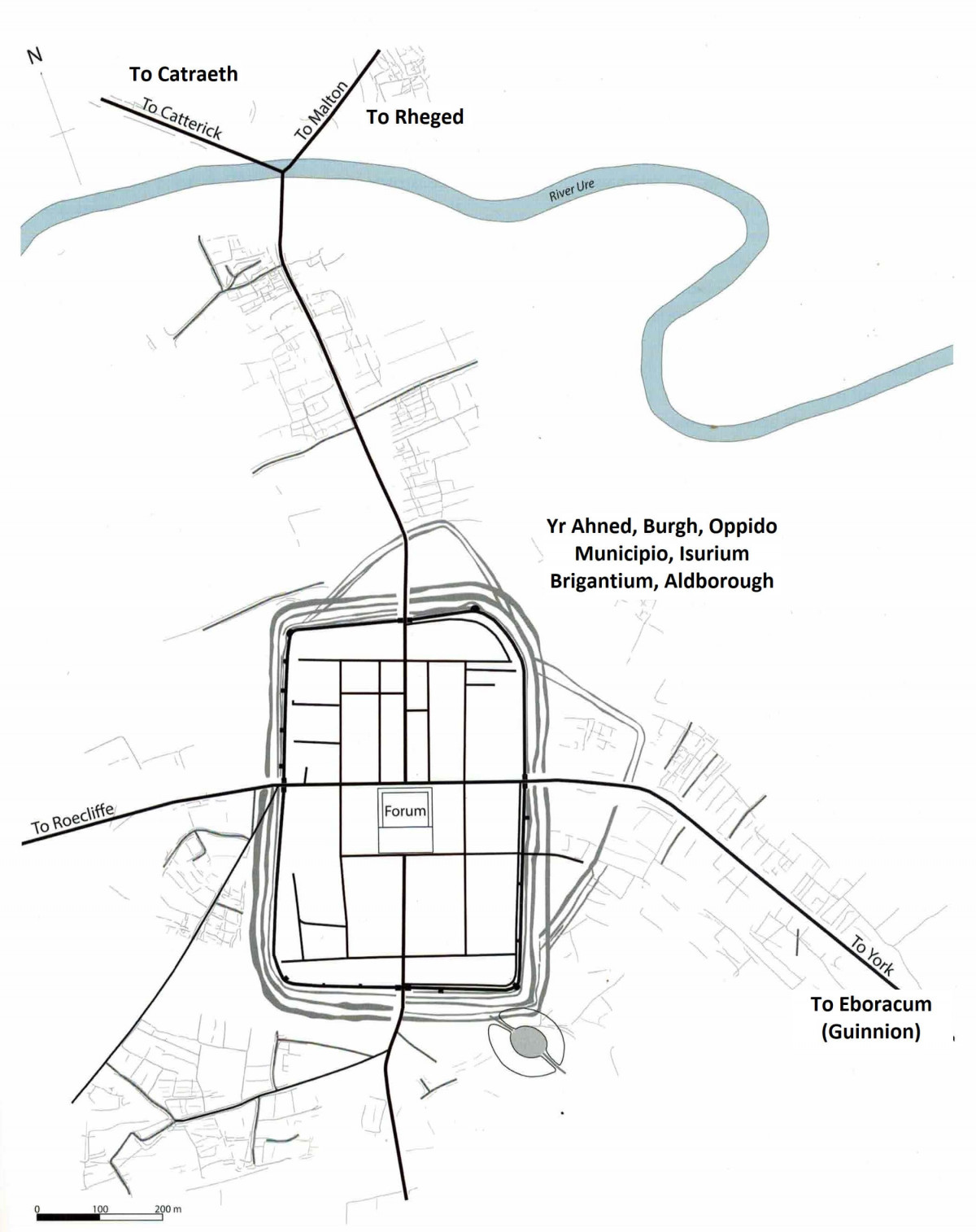

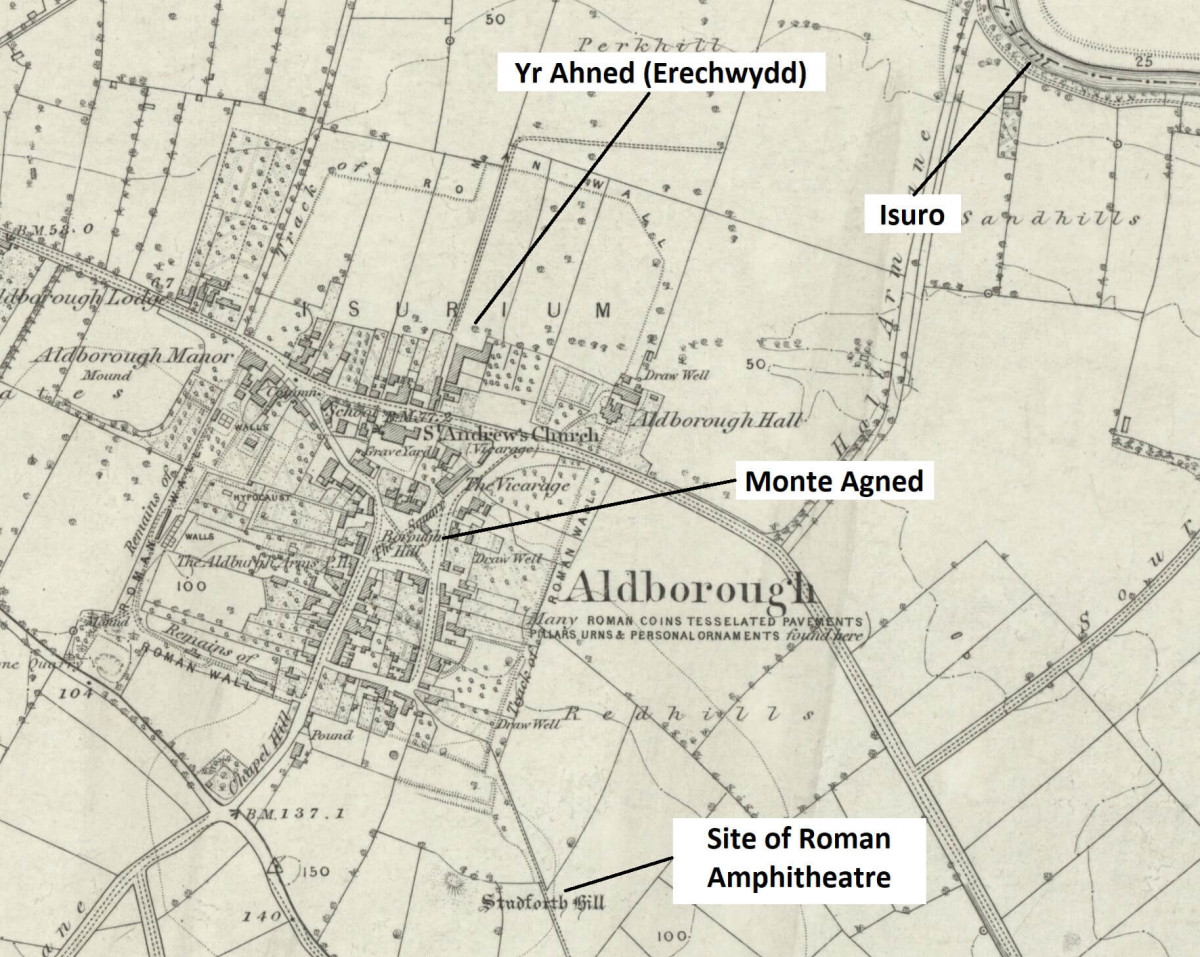

Erechwydd is Isuro, Isurium or as now called Aldborough. Originally, I rationalised this from the Welsh, being Yr or Ur Echwydd and meaning the fast-flowing Ure. Where I live has never really had a proper name and is really just called the settlement, the borough, the municipality, but does crop up a lot in early histories – obliquely but definitely there – for example Cadwallon probably camped here and beat Osric in 633/4 which was the last battlefield win of the British against the Anglo-Saxons. I accept that feels like a stretch, but the old Roman and post-Roman town has a road down its centre that crossed the Ure, and then turned northwest to Catterick or east to Malton. Importantly, Aldborough is as far as the Ure is navigable and was probably one of the most important local centres in post-Roman as well as Roman Britain. It commanded the route north. It has always been thus; it is basically on the road halfway between London and Edinburgh. Its importance is its position within the Vale and Studforth Hill, although small, commands the countryside around and about because the land is very, very flat here in the Vale of York.

At first, I thought its name, Erechwydd, could be a descriptive contrast to the lower part of the Ure that changes its name to the river Ouse near Great Ouseburn, where the much smaller Ouse Gill Beck flows into the river. For me, the Ouse is the Middle English name for Eirch, sounding similar, which becomes the Ouse via Danish (perhaps?) and the Arkle as in Arkendale in Old English. Others equate Eirch with Arkengarthdale which also could work, but for me Arkendale and the Ouse are more likely. Basically, the ‘Lower Ure’ is slower moving, so there is a riverine difference between the two elements of the river when you move on it.

Then of course, there is his name Urien, which echoes with the river name the Ure or the Isuron, or Isurium. This cannot be coincidental. Maybe, like the supposed names of other early rulers, e.g., Hengest, the name is as much a symbolic link to a more ancient, deeper ancestry than being real. But we will have to assume it was his actual name.

Then I looked at the original of Taliesin’s poems and I realised there was an alternative and much stronger argument for Aldborough. The usual version of the script is Erechwydd which is thought of as Er Echwid, but the script looks to me more like Er Enghwyd, i.e., Yr Ahned, so it means Urien of the Burh. As explained earlier, Aldborough does not have a real name and has always been known as the settlement, the burh, the burgh or borough, so was it called Yr Ahned in the fifth to seventh centuries? I think so.

What adds further weight to Aldborough as the location is that Cadwallon captured it and overwintered here in 632/3 and then beat Osric of Bernicia at a battle here in May 633. Bede calls the place oppido municipio, which means borough. And Cadwallon would choose to attack Aldborough because he was descended from ancestors from Rheged (or Gododdin) and brought up in Gwynedd on stories of Rheged told by poets like Taliesin and Aneirin and of his lost kingdom based in Ahned.

Now, Rheged. This is normally placed firmly in Cumbria and into Dumfries & Galloway. Because of this placement Catterick becomes a stretch to the east, so many argue its existence away as being a fabled battlefield or mythical name for a battlefield. However, if you shift Rheged to its rightful place in the Vale of Pickering then everything fits into place. This was the other keystone to the geography, the first being knowing where Erechwydd is.

Why the Vale of Pickering? Well, firstly the road from Erechwydd turns east to Malton which is at the exit from the Vale of Pickering into the Vale of York. The Vale of Pickering is a natural flat valley between the North York Moors- Cleveland Hills (also Howardian Hills) and The Wolds to the south. The Wolds then forms a natural barrier until the Humber further south and creates the Holderness region where the Anglo-Saxons first landed and were able to establish a permanent territory that would become Deira.

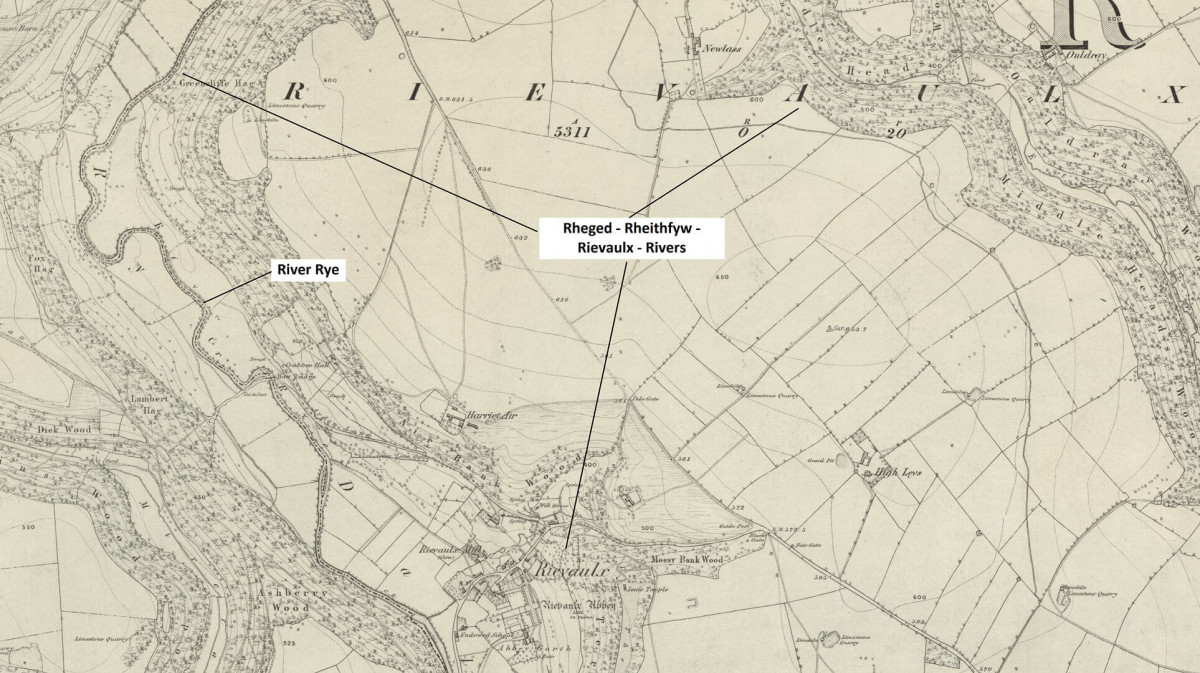

Secondly, within the Vale of Pickering, there is Ryedale. Ryedale is a curiosity because it is called Rievaulx in a section, which is pronounced in a French way as Reevaux or locally as Rivers or Reevoo. Traditionally, it is cited as deriving from the French for the valley (Rye + Valle gives Rievaulx), mainly because a monastery was set up in the early Norman period by monks from Clairvaux Abbey in France, i.e., they have similar sounding French names, and so the derivations were conflated. But I think it was actually the Frenchification of the old British for the valley, i.e., Reevoo or Reged. Sounds spurious, so I parked that idea for a bit.

But then I read ‘Y Gododdin’ by Aneirin and, in these, there is lament VII:

‘Men road to Gododdin, a rowdy troop,

band of brothers, a carousing crew,

their prop, the kindly Rheithfyw.’

So, this talks about the people from Rheithfyw, which when you look at the original online is written as ‘Reithuyw’. To me, that has to be the Welsh spelling for the word sounding like ‘Reefoh’. Indeed, ‘g’ can morph to ‘th’ and vice versa, for example, the people who lived in the region were called by the Romans the Brigantes and this is written in English as Brithones, i.e., the British. So, it is not the hard-sounding Reged but a softer Reefoh or something like that.

So where are we, we have Urien of Rheged (Reefoh) ruling both the valley of the river Rye and the Vale of York from Erechwydd-Isurium to Catraeth-Catterick, i.e., Ryedale and Wensleydale, which stretches from Whitestone Cliff across the Vale to Catterick on the west.

Next, there are the following lines in ‘Here at My Rest’:

‘Llwyfennydd’s people,

Arkle’s fighters,

Both great and small,

Join with one voice,

In the song of Taliesin,

Heartening them all.’

The first line is really: ‘Llwyfenyd van. Ac eirch achlan’, where Eirch may be Arkle. There is an Arkle Beck that runs through Arkengarthdale and flows into the Swale, the river at Catterick. However, I think this is describing the southern limit of Rheged and that this is the Eirch or Ouse which is roughly where the Vale of York enters the environs of York or Eboracum. Also, weirdly, the western end of the Ouse becomes Arkendale, so is the Ouse Anglo-Saxon and the Ark the Brittonic version of Eirch.

At some point, Urien must have pushed it further south to Airedale or the river Aire which is on the edge of Elmet. Taliesin talks about Aeron which must be Airedale or the river Aire, not the usually described Ayrshire; Ayrshire is only logical when Rheged is located in Cumbria but we have shifted its positioning further away, so this becomes a less likely answer.

Now, we are left only with the Idon, Llwyfenydd and the region around it. These are normally firmly located in Cumbria, so are the river Eden and the river Lyvennet. I toyed with the river Don as an alternative as it is also tidal like the Eden but could not get it to work.

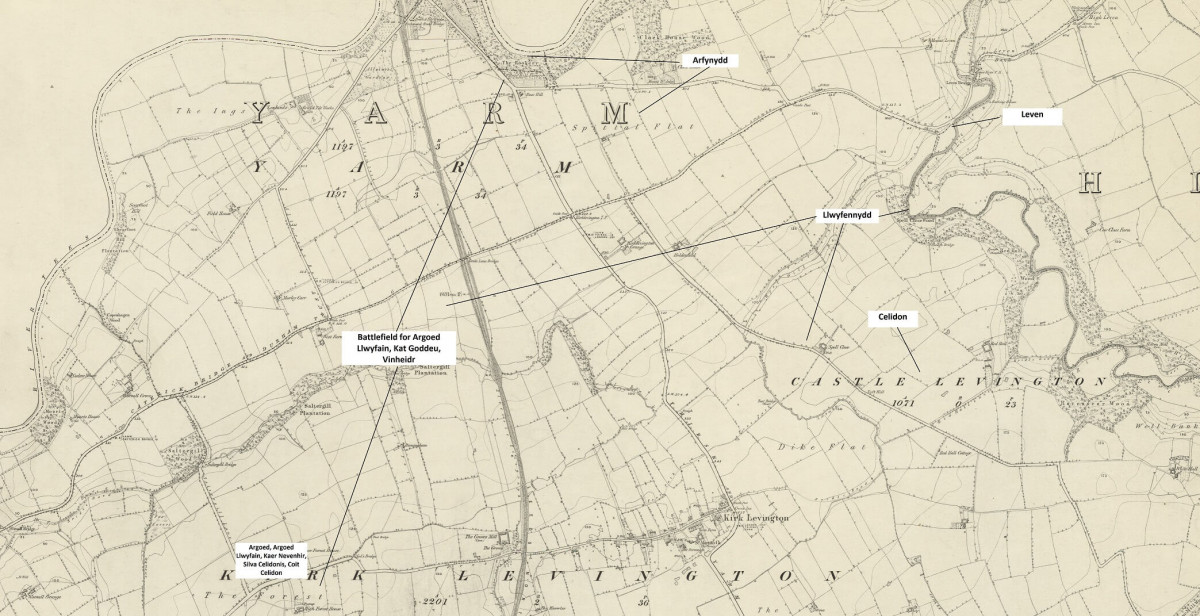

So, where is Llwyfenydd? This is the region around the river Leven, where ‘ed’ is a Brittonic ending that means ‘in the region of’ or ‘territory’. The river Leven flows into the Tees at Yarm. This location is important for lots of reasons, but there are two key ones: (i) the Tees is a natural boundary between Yorkshire/Wensleydale and Teesside and the boundaries of county Durham and North Yorkshire are around here; (ii) the Leven enters the Tees at Yarm which is the highest tidal point of the river and navigable. Then, the river sort of flows towards the North York Moors-Cleveland Hills so creates a trend line that neatly creates the edge of Wensleydale if we were to be using natural borders.

If we expand this idea further, ‘The Battle of Argoed Llwyfain’ goes:

‘Fflamddwyn marched forward in four battalions

To lay waste the lands of Goddeu and Rheged.

From Argoed to Arfynydd the muster was summoned’

Now, what makes the river Leven even more plausible is that there is a place here called ‘The Forest’ on old maps, so we have a patch between Arcoed-The Forest and Aryfynnydd, which I speculate means the confluence of the Leven and Tees at Yarm. This area has its Brittonic name preserved as Kirklevington and Castlelevington. This ghost wood presumably went from the Tees at this point and down the edge of the hills towards Thirsk along a river that is called Cod Beck. Traditionally, this is thought to mean ‘cold beck’ from the Yorkshire ‘cawd’, but I suggest it preserves the idea of Coed or Forest in Coed Beck and relates to the forest of the poems. I love a phrase like Coed Beck as it is Welsh plus Danish, so memorializes the history of the region – British and Danish.

I have two additional bits of evidence on this, which come from other sources: the Icelandic Egil’s Saga and Nennius’ stories of Arthur’s battles. Firstly, Nennius has Arthur fight his seventh battle at Celyddon Coed, which is normally explained as the Caledonian Wood in Scotland, but this is a long way away and seems to be our Coed Caer Llwyfenydd, i.e., the wood at Castlelevington, whose place name preserves the old Brittonic names in English, so literally we go Old British to Old English. Then, we have Egil’s Saga where Egil Skallagrimsson fights the Scottish king Olaf the Red at a site often thought of as Brunanburh. However, this battle is fought at a place called Vinheiδr, which is normally translated as White Heath or Wen Heath, but I think it is simply an Icelandic translation for Llwyfenydd.(i)

Before we go on to Idon, I think that the reason lots of battles were fought at Catterick and Castle Levington is that battles were perhaps fought at ritualistic or suitable, strategic places, or maybe they are just the same battle retold with new protagonists. For example, I think Arthur’s and Urien’s battles and ‘The Battle of the Trees’ seem to be the same fight; indeed, Egil’s Saga seems very similar as well. I think it was Urien’s battle that was the real battle of the Britons, but it has been coopted by others, except, as discussed in yesterday’s blog, I think Gwydion in Cat Godeu may really be Urien. As for ritualized battles, like Egil’s Saga, the battlefield was laid out with hazel rods in a formalised way and so these places may have been where disputes were settled in a regularized way. So, the idea that Catraeth becomes a mythical battlefield could be right because a dispute between Rheged and Strathclyde, for example, would be fought and settled at this designated battleground. I suppose it is a bit like the contests of the Greeks, where you would try and settle the battle by having two heroes fight against each other first. I admit that is highly speculative.

If we go back to Egil’s Saga, it seems to explain the words in the Taliesin poem very neatly as the place to muster your troops in a battle here at Vinheiδr-Llwyfenydd: ‘The site had to be chosen carefully, since it had to be level and big enough for large armies to gather. At the site of the battlefield there was a level moor with a river on one side and a large forest on the other. King Athelstan’s men had set up camp over a very long range at the narrowest point between the forest and river.’ This is spookily close to 'Argoed to Arfynydd'.

There are lots of candidates for Egil’s battle, ranging from Bromborough (Brunanburh) to Brassside to Bramham to Hunwick, but I think it is the same battleground again as in Nennius and Taliesin.

Indeed, I am going to boldly assert (absolutely no proof available!) that there was no battle fought by Egil at Vinheiδr but that the saga has lifted a story from British legend and claimed it to himself. I think that Egil’s battle, ‘The Battle of the Trees’ and Arthur’s battle at Celyddon are all the same battle fought by Urien at Llwyfenydd.

Finally, if we revert to ‘The Battle of the Trees’, this is located in a mythical place with its battle fought at Caer Vevenir (Kaer Uefenhir) when and where the Lord of Britain fought a great battle. This is once again Vinheiδr or Llwyfenydd or simply Castlelevington – which I admit does not sound so mysterious, mythical or exciting. Although it would be nice if it was about the forest that was located here, it does not mean that the poem was written about this wood but that the poet used it as a mythical poetic space, because it was the place of the legendary Battle of the Britons!

What is a curious similarity between Taliesin’s ‘The Battle of the Trees’ and Egil’s Vinheiδr is that both include a trick, which in the first is about co-opting trees and the second about putting up extra tents. So, I wonder whether it was remembered in stories that Urien tricked the Prydein (people from Scotland, but not Scots) by perhaps using the wood and its trees somehow – it echoes down the ages into Macbeth with the moving Birnam Wood at Dunsinane Hill – and that ‘The Battle of the Trees’ conflates Urien with the miraculous, so Urien becomes Gwythion who brings the trees alive.

Secondly, Idon. It is mentioned in a line in ‘The Men of Catraeth’ - ‘Drunk and dazed on the Idon’s red wine’ which is usually linked to river Eden in Cumbria. I think this could be Castle Eden Burn but may even be the Tees itself. As for the idea of the Tees first. The area here was called Dunum Sinus in Latin. Indeed, the idea of ‘vinum rubrum’ from ‘dunum sinus’ may have been a wordplay. This may relate to the area or the river itself and so we have a tidal river called the Idon, perhaps. I prefer the idea that the Idon is Castle Eden Burn, but then again Yarm is where the Leven and Tees meet and is where boats were loaded and unloaded for many centuries before shipping became bigger and moved to the mouth of the Tees; this could be a port area. Is this where red wine came in from the Roman empire to slake the thirst of weary travellers, trudging up and down Dere Street? Intriguingly, the only mentions of Aldborough in Roman times are as a place to get wine on the road between York and Corbridge.

As an aside, the derivation of Yarm is normally given as from the Anglo-Saxon ‘gearum’ meaning ‘at the place of the fish pools’, but I wonder whether it is really Brittonic and is ‘Y Ar + something’, so a shortened ‘Arfynnydd’. ‘F’ and ‘m’ do mutate in Welsh, so Y Ar Fynnydd could become Yarf then Yarm.

Sorry, back to Eden. I think this is more likely Castle Eden because I think the Caer Eidyn in ‘Y Gododdin’ is not Edinburgh but Castle Eden. I will explain this in my next blog.

A possible counterargument to my geography is that the poem ‘Rheged, Arise, its Lords Are its Glory’ does not fit into this landscape. My view is that this poem is not contemporaneous with the other Urien poems. It was perhaps used to stir up the fighting spirit of the former inhabitants of Rheged by reminding them of their past glories. It may have been a poem composed for Cadwallon before he advanced into Yorkshire later, so copied the style of Taliesin, and was designed to remind the people of Rheged living now in Gwynedd of Urien and their former fighting spirit. For example, ‘Rheged, arise, its lords are its glory. I’ve watched you, though I’m not of you’ suggests the composer is not from Rheged but knows the people of Rheged, i.e., he is a composer from Gwynedd but knows the people formerly from Rheged who are now living in Gwynedd as exiles, and ‘Till Urien in his day took Aeron, There was no fight, it wasn’t welcome’ seeks to remind the people of Rheged of their heroic past.

Anyway, to finish up, we have something along these lines: Urien was born in Ryedale, which was his stronghold, then took over Wensleydale and operated his realm from Isurium-Yrahned-Burh, and that Wensleydale or the Vale of York was bounded to the south by the Ouse-Eirch or Aire and to the north by the Tees-Leven and to the east by the North York Moors-Cleveland Hills and Wolds and to the west by the North Pennines. This is a much more compact region than the standard placement of Rheged and is located here in North Yorkshire from the Ure to the Tees, rather than in Cumbria-Galloway-Catterick.

Notes

23/2/2023: Reading Ifor Williams' notes on 'Lament for Owain, Son of Urien', there is a line that has been translated as 'prince of joy, prince of brilliance' but I prefer Ifor Williams' version that is translated as 'prince of the beautiful Llwfenydd', i.e., the region around Yarm and the river Leven with great importance to the Rhegedian memory.

17/3/2023: I have been corrected on my translation of Er Echwydd. It is 'on' or 'in front of' 'the fresh water' so my idea of it being Ahned is rubbish. It does though allow a reinterpretation of Arthur = Ar Dwr = Yr Echwydd = On fresh water.

References

The best starting places:

Gillian Clarke (2021) ‘The Gododdin: Lament for the Fallen’, Faber & Faber, London.

For a deeper dive:

Sir Ifor Williams, translated by J. E. Caerwyn Williams (1975) ‘The Poems of Taliesin’ The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin.

The Book of Taliesin, National Library of Wales, Cardiff.

The Book of Aneirin, National Library of Wales, Cardiff.

Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett (2020) ‘Isurium Brigantium: An Archaeological Survey of Roman Aldborough’ research report of the Society of Antiquities of London No. 81, London.

Thomas Williams (2022) 'Lost Realms', William Collins, London.