21 February 2023

Yorkshire Really Is God’s Own Country

Aneirin's lament for the fallen soldiers at the battle of Catraeth rings through the ages. Based on my previous blog, I analyse the poems in the new geographic landscape to explain where I think Gododdin really is to be found.

Gododdin and Goddeu are two other realms mentioned in this period. Goddeu is unknown, but may be it is another name for Gododdin, which is generally regarded as the Eastern Scottish Lowlands, with its fortress at Dun Eidyn (Edinburgh), and as having territory that ran south towards or beside Northumbria.

Its foundational poem is ‘Y Gododdin’ by Aneirin, a contemporary of Taliesen. Nennius recorded that at the time of Vortigern, ‘Aneirin and Taliesin and Bluchbard and Cian, known as Gueinth Guaut, were all similarly famed in British verse.’

These poems have been beautifully translated by Gillian Clarke in her recent book ‘The Gododdin: Lament for the Fallen.’ I love the way each poem is structured, the words are haunting and ring across the ages, and it is brilliant that the Welsh is printed opposite the English, so the two can be read side-by-side.

The laments could be for the soldiers who fought alongside my grandfather in Ypres and have the melancholic sentiment of lives cut short, for example:

‘Ceredig, celebrated, famed,

loved life dearly, as his name tells –

favoured, favourite, till his day came.

Quiet and courteous,

may he who loved song find his place

at home in Paradise.’

However, let’s return to the task of geography.

Firstly, the poems seem to back up the concept of a battle of Catraeth, which I don’t see as merely a mythical place that just means ‘battle-shore’, a compound of ‘Cat’ meaning battle and ‘Traeth’ meaning shore. The argument against Catraeth actually being Catterick revolves around the convoluted way that Cataractonium goes via Cadarachta to Cetrecht to Catraeth then Catterick, but this misses the fact that it is not spoken as three syllables but is pronounced ‘Catric’, then a ‘c’ can mutate in Welsh to ‘ch’ which is pretty close to Catraeth. Then, in addition, as in my blog from yesterday, there is a plausable bunch of braided, sandy banks and islands on the Swale below Catterick, complete with ford, so there is a Catraeth at Catterick which works very well for a poet’s word play.

A second argument against Catterick is that, because Rheged is assumed to be in Cumbria, Catterick is a long way away and over the Pennines from Carlisle. However, if as I have argued, Rheged is within the realm of North Yorkshire with its urbs regia at Aldborough, there is no reason for Catraeth not to be a few miles up the road, just off Dere Street.

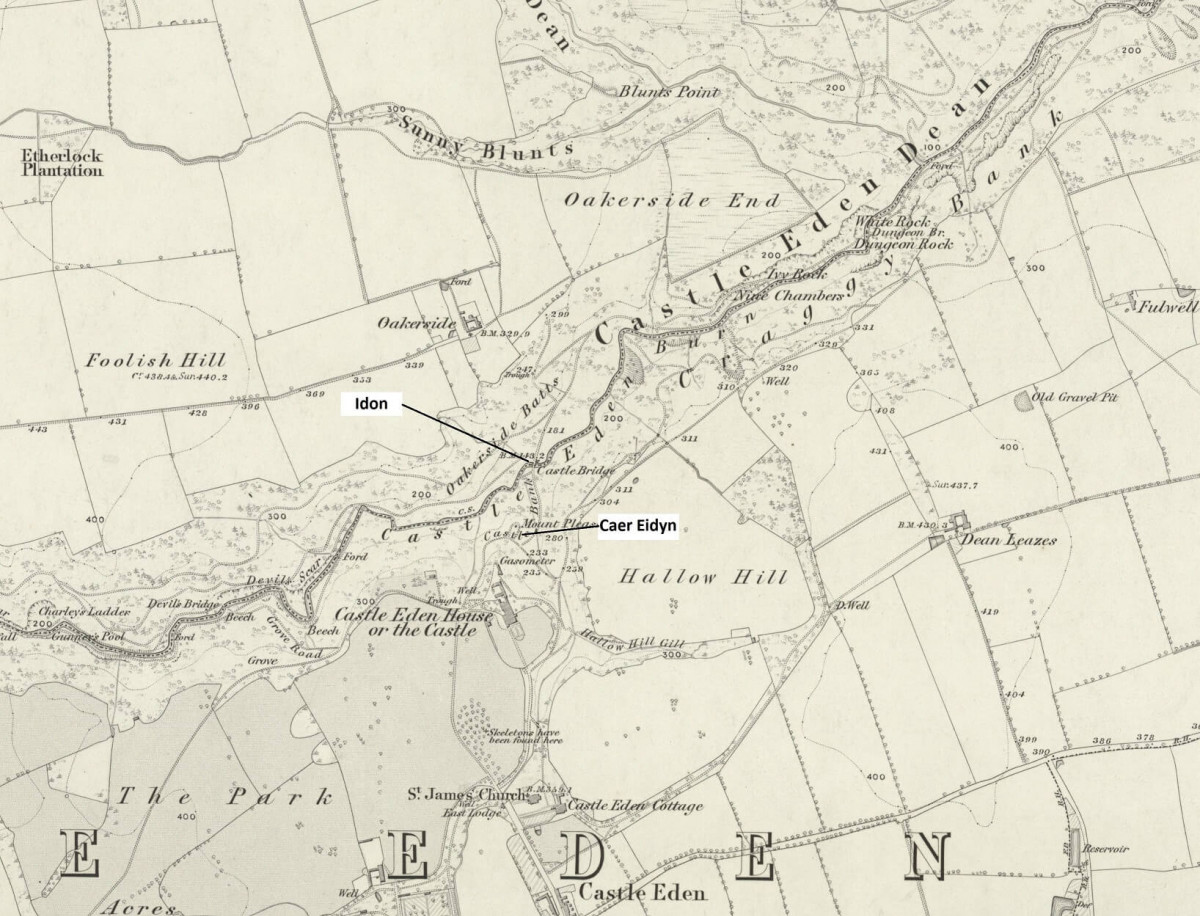

Further, if Rheged is Rheithfyw or Ryedale and Gododdin is really Teesside, everything becomes a lot closer and more sensible. Yes, I reckon Gododdin is not a Scottish kingdom based around Dun Eidyn (Edinburgh) but maybe a Northern lordship centred on Castle Eden in County Durham (see map below). If Gododdin is Teesside, then there is no reason why the soldiers who fled from Lindisfarne in c. 587 after Urien was killed would not drown their sorrows at Castle Eden, then hatch a plan to launch a swift attack on the Anglo-Saxons who had captured Catterick in their absence. It is much more of an imaginative stretch for them to retreat to Edinburgh, get drunk then launch an attack that needs them to ride towards the Clyde, then down to Carlisle and over the Pennines – not a lightning attack and you’d have been very sober by the time you reached Catterick. Much more likely you rode the 50 miles across friendly North Yorkshire, without time to realise you were hopelessly ill-prepared.

If Gododdin is around Castle Eden, then the following lines work very well:

‘Men road to Gododdin, a rowdy troop,

band of brothers, a carousing crew,

their prop, the kindly Rheithfyw.

Their blades brought silence.

Men rode to Catraeth, debonair,

their snare, the honey-trap, gold mead.’

What else makes me think that this is part of Rheged-Wensleydale rather than Scotland? There is a similar poem to the above, where the battle is seen as happening over five days from hatching the plan to all being killed. Okay, there is likely a lot of symbolism and poetic licence in the timetable, but there is the sense of a hastily constructed battle plan that needed more preparation, because the results were catastrophic, whereas a measured ride for 300 miles or so over a couple of months would have given much more time to develop a better strategy, or indeed dampened their collective enthusiasm. It really seems like a case of ‘fail to prepare, prepare to fail’ writ very large.

Perhaps, though it is lines like the following that give the sense that Gododdin was close to Catterick:

‘Usually on a spirited horse, fighting for Gododdin,

ahead of the bravest in the action.

Usually hunting, swift on the deer’s track.

Usually before the Deiron army he’d attack.

Usually trusted, the word of the son of Golystan,

though not a prince.

Usually, for Mynyddog, shields were shattered.

Usually his spear was bloody, Urfai, lord of Eidyn.’

These lines suggest that Urfai fought against Deira, which was located in the south of Northumbria between the Humber and York not in the North, so Gododdin must be south of the Tyne. So, the lord of Eidyn must have been around Rheged which I have suggested above is Castle Eden in County Durham.

Interestingly, in 632/3, Bede writes that Cadwallon forced a villa, Campodonum, to provide his army with supplies. Normally, this is thought to be around Dewsbury or Cleckheaton, but to me it sounds like Castle Eden again, even though 'campo' is a field in Latin but maybe it was a a mistranslation into Latin of 'caer' 'edonum' or Castle Eden. It fits with what Cadwallon seems to have had as his mission, i.e., to recover and exact revenge for the loss of Rheged and Gododdin.

Indeed, if we go back to Taliesen, ‘The Battle of Argoed Llwyfain’ goes:

‘Fflamddwyn marched forward in four battalions

To lay waste the lands of Goddeu and Rheged.’

This makes much more sense if Fflamddwyn (Theodoric of Bernicia) was marching southwards to North Yorkshire and laying waste to Teesside and Wensleydale, rather than splitting his forces and marching north to a Scottish Goddeu and south to North Yorkshire’s Rheged. It does not really work either if Rheged was in Cumbria, because your soldiers would march either north on Dere Street to Scotland or west to Carlisle on Stanegate, so there is no military logic in doing both simultaneously and having to split your four battalions in two.

Then, there is a beautiful poem at the end of the book that is not one of the poems of Y Gododdin but is supposedly by Aneirin. In this, Dinogad is remembered:

‘He hunted on the mountain wall

for freckled grouse, a doe, a deer,

fish from Derwennydd waterfall.’

There is no Derwent in Lothian, but there is one in Ryedale and another in county Durham. I like to think this waterfall may be Wharnley Burn Waterfall at Castleside, as I regularly drive this way to visit my mum. This is close to one of my favourite place names in the world, Wallish Walls - what a name?

So, for me, ‘Y Gododdin’ conjures up the idea of a small lordship in Teesside that may have been subordinate to the Rheged-Wensleydale realm of Urien. Here, the Lord of Eidyn (Castle Eden) was a good host, renowned for entertainment, red wine, mead, poetry, and had a strong martial spirit.

I see the North Britons as living in an arc from Gwynedd in North Wales through Elmet (if it existed in its own right) and then up Wensleydale to Teesside and maybe up to Corbridge – this is the patch of Y Hen Ogledd, the Old North. This is very different from the standard framework which goes up via Cumbria along the Roman Wall and up into Northumberland. On this basis, it is unsurprising that within the Gododdin war-party, there are quite a few soldiers from Aeron and Gwynedd as well as from within Rheged-Gododdin. This is much more plausible than if Rheged was located along the west coast around Carlisle and into Dumfries and Galloway. Indeed, Gwynedd had a very close relationship to Gododdin as the leadership was descended from Gododdin ancestry, i.e., they are one and the same kinship group.

For example, within the ‘Y Gododdin’ poems, Cynddilig, Cynon, Cynrain and Cynri came from Aeron (is this Elmet?) and Cadfannon, Cydywal, Gorthyn Hir, Isag, and Owain, Gorthyn came from Gwynedd. The band from Gwynedd was led by Gorthyn Hir:

‘True son of a king, proud boar,

lord of the men of Gwynedd,

of the bloodline of gentle Cilydd.’

Finally, as a highly speculative word play, is the origin of that highly aggravating phrase, ‘Yorkshire is God’s own country’, a relic of the phrase ‘Yorkshire is Goddeu’s Country’ or even ‘Yorkshire is Gododdin’, because ‘din’ and ‘dun’ mean hillfort, place, settlement, refuge, etc.

Enough said. I’ve written too much on this – buy Gillian Clarke’s book, it’s beautiful.

My train of thought continues with an analysis of Nennius' Battles of Arthur.

References

Gillian Clarke (2021) ‘The Gododdin: Lament for the Fallen’, Faber & Faber, London.

Images

Castle Eden Dene, Mike Kipling Photography/Alamy Stock Photo (2010), Purchased and downloaded from Alamy with website licence (20/2/2023).

Wharnley Burn Waterfall, Clearview/Alamy Stock Photo (2013), Purchased and downloaded from Alamy with website licence (20/2/2023).