21 February 2023

King Arthur Was A Northerner - Of Course He Was!

Having already gone where only fools fear to tread, I have read Nennius' accounts of the battles of Arthur and have managed to unpick the secret in the text. Really, I have.

So, let us carry on this mad journey. I decided, as you do, to read Nennius’ ‘Historia Brittonum’ because it talks about Aneirin, Taliesen and Urien. It, amongst other things, also records Arthur’s battles. [I have made quite a few changes since this blog - the updated blog is'Nennius and Arthur's Battles Revisited: A Map of The Old North' but the core argument remains the same.]

Anyway, I soon realised these all interlink with each other as they are closely related stories, all with the same purpose – to preserve a memory. Also, I realised that Nennius was having a bit of a laugh or at least there was a bunch of clever in-jokes going on in Latin. The problem is that everyone has been reading Nennius’s work, or at least, the section on Arthur too seriously – yes, he may be talking about real battles and a real history, I don’t know, but his battles are at one level humorous but at another a very serious oral evocation of Rheged.

I suppose it is a secret story hidden within the text for those in the know. Indeed, that is how I see Taliesin and Aneirin, they are really about memorialising a place, in terms of its boundaries, its towns and its battles. The language is beautiful, the poetry intricate, but it is secondary to the locations – this is first and foremost oral history and oral geography.

What is fun about this is that my answers are totally different from anything else anyone has come up with – that is somewhat scary!

The secret to unlocking the code or that there was even a puzzle here was this line:

‘Secundum, et tertium, et quartum, et quintum super aliud flumen, quod dicitur Dubglas, et est in regione Linnius.’

Generally, this river has been regarded as ‘unidentified’ or any of the river Douglas on Loch Lomond or the river Trent, or Devil’s Water in Northumberland, etc., etc.

The problems with the standard interpretations of this passage in Nennius are: (a) reading it literally rather than as a puzzle or an in-joke; (b) reading it in English rather than Welsh because Nennius spoke Welsh not English, so you need to go back and forth in Welsh and as far as I know there is not a Welsh translation of Nennius; (c) thinking of the landscape as the UK as a whole rather than the much smaller area of Rheged, Gododdin and North Yorkshire, Teesside, Weardale and County Durham.

The answer, though, is remarkably simple, but first, you need to translate the Latin into Welsh and accept that we are talking about the North only and Rheged specifically – those are the limits to the geography.

So, Dubglas becomes Duglais or Dulais and means the Dark River or Watercourse, or the Shade River, which in Latin is Umbra (dark, shadow), so this is the Humber. The Humber is beside Lindsey or Lincolnshire, so it is easy to envisage Arthur fighting lots of battles (his second, third, fourth and fifth) against the Anglo-Saxons as they came up the Humber to settle the region that would become Deira. Clearly, he deterred them from Lindsey, but they managed to settle on the northern shore near Hull.

If I can explain this idea further, let’s think about Fort Guinnion, the eighth battle, which is often associated with Binchester. But look again at the words, the Latin is Castello Guinnion, so we have three parts: ‘fortress city + guinn + on’, where ‘guinn’ is ‘gwen’ which is Welsh for white. That much is standard, so on Wikipedia it is called The White City. By my unpicking of the wordplay, the town is York, because ivory is white and is ‘Ebur’ in Latin and the Roman name for the military fortress of York was Eboracum or in Brittonic Eburākon. Then, the idea of an icon of the Virgin Mary on Arthur’s shield in this battle is a play on the word ‘icon’, which rhymes with ‘akon’, i.e., there was no actual divine intervention, but the word play becomes another bit of humour or the coding. So, like in a crossword, we have Ebur + Icon, so Eburākon or Eboracum.

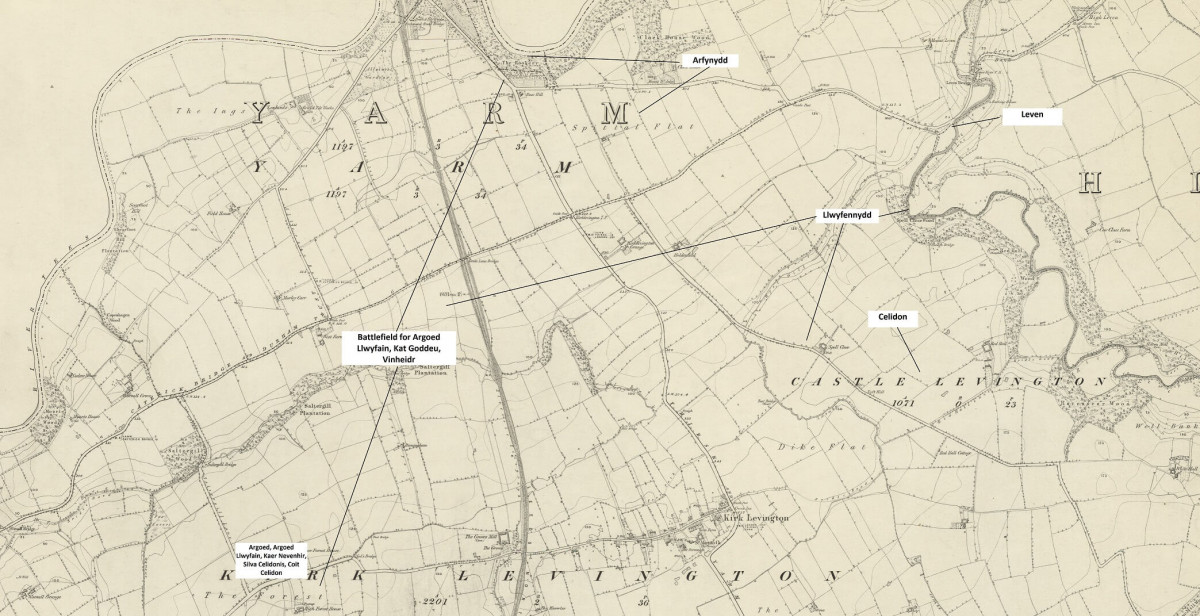

Some of the other battles are actual places rather than wordplays. So, we have the seventh battle at silva Celidonis which is at Coit Celidon, which is normally located in Scotland at the Caledonian Woods in the Scottish Lowlands. However, as already discussed, Cat Coit Caer Liddon is the Battle at Castle Levington or Cat Caer Llwyfenydd, which is in North Yorkshire near to Yarm. This is, also, the locations of Urien’s battle, Cad Godeu (The Battle of the Trees), and Egil’s battle at Vinheiδr.

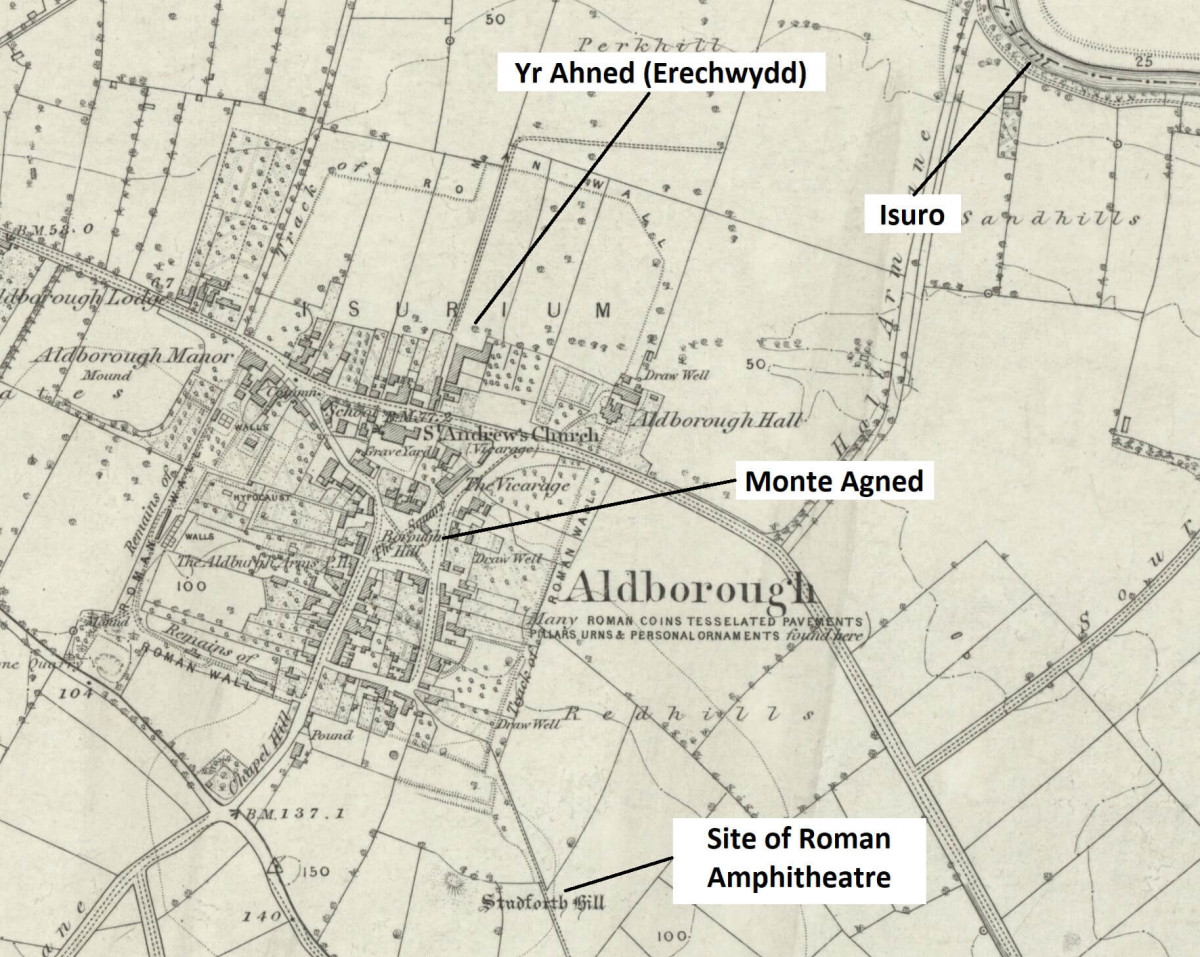

Next, we return to the keystone to this landscape, the settlement, the burgh. The eleventh battle is fought on Mount Agned. This is variously thought of as Mount Agned which is supposedly another name for Edinburgh, with the Roman fort Bremenium at Rochester, Northumberland, another possibility.

I live in a strange place – it is a place that has no real name throughout history, it has a generic name but actually it has no proper name, and throughout history is just known as the settlement, the burgh. Even in Domesday, it was simply recorded as ‘Burgh’. What is the relevance? Agned is Ahned which means ‘dwelling place’ or ‘settlement’, so it is the Burgh or as it is now known, Aldborough. And indeed, I live on Burrough Hill, then there is Studforth Hill where the old Roman amphitheatre was. It is not much of a hill, but it is the old Roman road that went through the town, crossed the Ure and turned north to Catterick (Catraeth) or east to Malton (Rheged). Indeed, as mentioned in a previous blog, the Welsh in the Urien poems might not be Yr Echwydd but Yr Ahned, so he is Urien of the Burgh. As I have written earlier, these stories and poems support themselves, they are one cultural history.

I am not yet convinced that Arthur is a person, but more a people, a place, a history – Arthur is the symbol for the Britons, the Old North, for Rheged, and he is embodied in Urien. Arthur and Urien are ‘Y Hen Ogledd’.

So, I am pretty certain of the identities of the Humber, York, Aldborough, and Castle Levington.

Next, we have some less precise places. They are in the right areas but pinning down the logic is proving tricky, but the people of Rheged would have known, they would have understood the metaphors.

Let us begin with the ninth battle which is the Battle of the Town of the Legion. First remember we are in the Northeast only as this is sounding out the boundaries of Rheged. It cannot be York as we have already done this, so I reckon it has to be either Piercebridge (Morbia) or Corbidge (Coria). My gut instinct goes for Coria because you both have the old military base for the Legion at Corstopitum and the established township of Coria. Also, Coria is at the northern limit of Rheged at the end of Dere Street and is a strong place militarily - Corbridge guards the crossroads where the Roman Stanegate leads west, parallel to the Roman wall through the Pennine gap at Gilsland and where Dere Street runs north through the wild fells of Cheviot towards Edinburgh and Strathclyde. Furthermore, the Roman bridge here commands a critical crossing of the river Tyne at its highest navigable point and was likely functional in the sixth century, or, if not, the river can be forded just downstream.

It cannot be the alternatives listed on Wikipedia, because the places can only be in Rheged and nowhere else. That having been said, it could be York again, but if we are describing the boundaries of the Old North in this passage, then we need to include Coria as the northern tip. What adds a bit of weight to this idea of Corbridge, rather than just my speculation, is that Cadwallon sets up here after winning the battle in Aldborough in 633. It is here where he receives Eanfrith for a parley and kills him and his companions in May 634.

Why is this significant? Cadwallon claimed Rheged by birthright, so this is not just a random campaign, Cadwallon was descended from Cunedda of Gododdin. So, after Rheged and Gododdin were defeated at Catterick in 588, the remnants of the ruling group scuttled off to their cousins in Gwynedd, together with their bards, Taliesin and Aneirin, where the stories of their lost kingdoms were preserved for posterity. Cadwallon was brought up on these stories and wanted revenge. So, it is totally logical for him to seek to reclaim them from the Anglo-Saxons; first, Aldborough was taken as this is the urbs regia of Rheged, then Coria because that is at the northern tip of its territory. It, also, explains why Oswald had to fight against Gwynedd and Mercia, and would be killed near Oswestry in 642, because he needed to defeat and wipe out the descendants of Gododdin who were the rightful rulers of the Old North.

Speculating even more wildly, I wonder whether St Wilfrid, ever the meddling priest, founded monasteries at Hexham and Ripon specifically to create new power bases near to Coria and Aldborough, so seeking to shift power from the Old British power bases to new Anglo-Saxon bases.

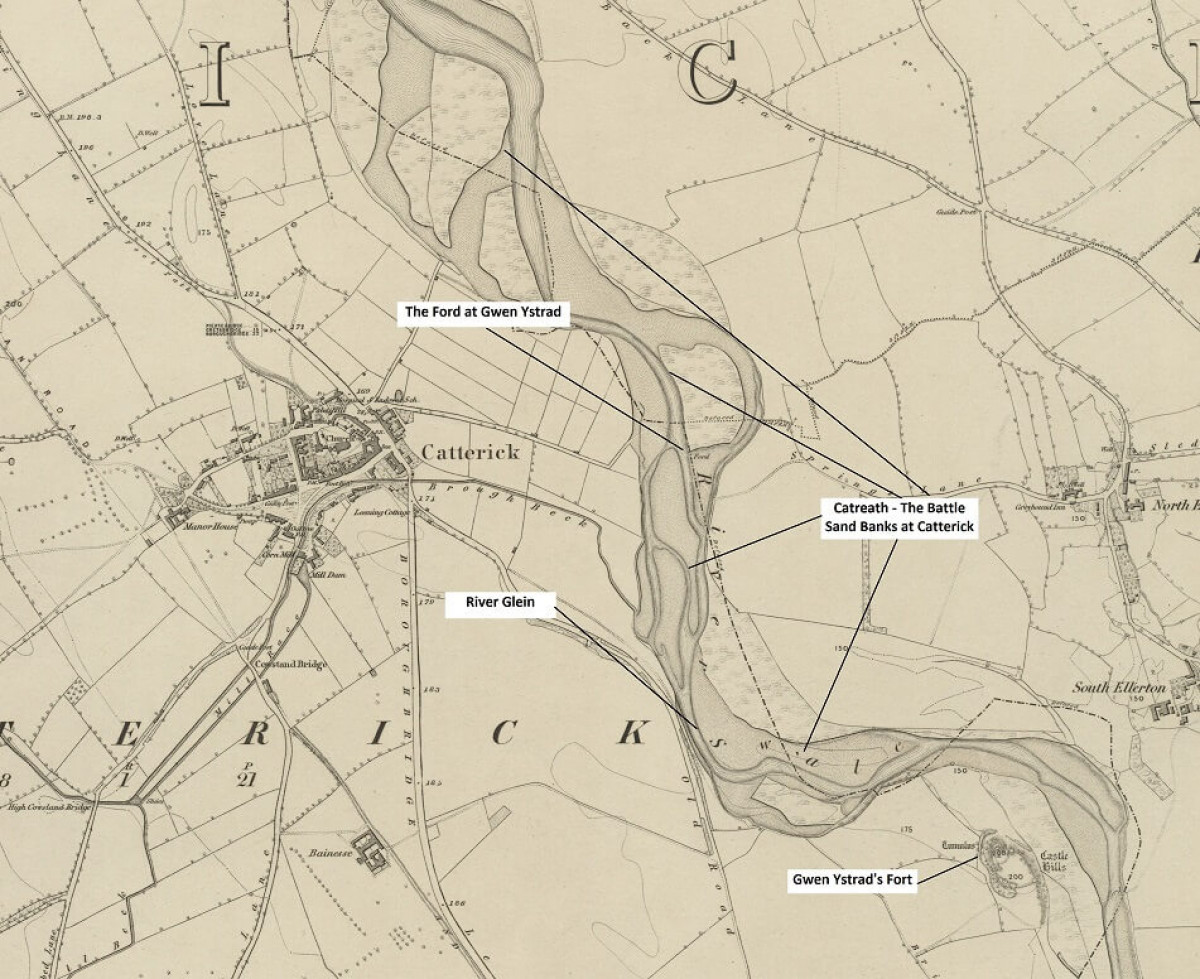

Next, the first battle at the river Glein. Normally, this is the river Glen in the Cheviots or the river Glen in Lincolnshire. Both are too far away for my analysis, but the Glen in Northumberland runs close to Yeavering Bell, so has strategic logic as this was the seat of the Anglo-Saxon invaders, who founded Bernicia, and beating them back would have been a sensible military objective. However, I think it is a play on words again. Glen is a valley, so means the river in the valley or gwen ystrad, i.e., Wensleydale, and valley in Latin is ‘valles’. If you shift the ‘s’ from the back to the front, you get ‘svalle’ or the river Swale, which flows through Catterick, and we all now know that Catraeth was a battle fought in Rheged and had great symbolic importance to the Old North and the Welsh through Aneirin and Taliesin. So, Glein is the Swale.

Now, there are two other rivers the Bassus and the Tribuit. These have caused me headaches, but I think I can answer them, but these are even more speculative.

If we begin with Bassus, this is normally linked to Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth, or maybe the river Witham at Bassingham, the homestead of Bassa’s people. An alternative northern location is at Bassington on the River Aln in Northumbria, not far from the river Glen. However, I think it is a puzzle again, so Bassus is Basis in Latin which means foundation, which in Brittonic is ‘wotād’ or the river of the Gododdin, sometimes Idon, or the Tees. This explanation of wotād is given in an earlier blog, where I explain that Goddeu is Teesside-North Yorkshire and it is best to think of it centred on the river Eden or Idon, which echoes in the Latin for the region, i.e., Dunum Sinus, which maybe the name for the tidal part of the Tees-Leven. This does cause a query as to where Castle Eden is located but I will stick with my earlier positioning.

Next, the river Tribuit. I have struggled on this. The normal is to say that the Latin is a miscopying Tyrfrwyd, which is interpreted as ‘rushing water, a flood’, so the Solway Firth, the Firth of Forth or the river Avon near Bo’ness or Dumfries. My thought is that it is ‘Tri’ meaning three or many and the word ‘Buyd’ which means ‘bend’ or ‘bow’, so it is the many bended river – this may then be the river Wear, which comes from the Brittonic word ‘Wejr’ which means ‘bend’ as well. It may even mean the three bends that circumvent the central hill of Durham and could indicate the exact location for the battle, itself, at Durham. It is likely that Durham is Gaer Weir in Taliesen, so it seems plausible that this was an important site for Rheged.

Arthur’s final battle where he was killed is called Camlann. This is tagged into the Welsh chronology rather than the text of Nennius. The most likely location is Camboglanna on the Roman Wall. This feels too far to the west for me, but we will live it for now. That having been said, and running on from the idea of Gaer Weir, it could be Cwm Llan and mean ‘the hill of the church’, so is this Durham, i.e., Gaer Weir? However, I am not that convinced that this battle was originally included in the histories but was added in later.

Finally, we have the battle on Mount Badon. This is another place that I am 100% certain of its location, but I have left it till the end because it is foundational for this whole narrative. There is a long list of possible places on Wikipedia, with Solsbury Hill near Bath being the leading candidate, with other alternatives being Bowden Hill in Linlithgow and Mynydd Baedan in South Wales. However, Mount Badon is clearly the same place as Manaw Gododdin and is Roseberry Topping in North Yorkshire. In 1149, Roseberry Topping is recorded as Othenesberg, so Mount Othenes, which is close to Badonis in sound. Then, if you look at the word in Nennius, it may not say Monte Badonis, but really be Uadonis or Vadonis, which is possible and ‘b’ and ‘f’ are mutations of each other in Welsh, so it could be a soft ‘v’ which is more like an ‘f’. So, I think, here we have Mount Guotod, that becomes Manaw Gododd, or Ododd. In Y Gododdin, Gododdin is sometimes written as Ododdin without the G, so it may be a silent first letter and so we have Uadonis.

So, to reprise the idea of Gododdin and Caer Eidyn. It now seems that the central point of Gododdin, Manaw Gododdin, is not in Scotland but is Roseberry Topping. So, the spiritul heart, the solium paternae antiquitas, the ‘seat of paternal antiquity’, of the realm of Goddeu is this hill. If you look at Roseberry Topping, it has a shape that evokes a deeper side to life (see image at top of blog). Then, the river Leven also begins on Roseberry Topping and, as already discussed, the Leven is important to the psyche of Rheged.

When Urien fights in Manaw, which means hill, I think he is defending Roseberry Topping not off in Clackmannanshire in Scotland or the Isle of Man. Indeed, it may even be that Caer Eidyn is on Roseberry Topping, so the Gododdin could have got drunk on mead here not Castle Eden, which is only 30 miles from Catterick. Also, returning to Cadwallon, he is a descendant of Cunedda from Gododdin, so of course he would fight and conquer Northumbria, because it is his by birthright as his genealogy came from North Yorkshire not Scotland.

So, there we have it. Nennius records that Arthur lived and fought battles in the North, centred in Rheged-Gododdin, which is delineated as from the Humber to the Wear, then from Roseberry Topping to the Swale, and has the Burh or Aldborough as its central town, with other important places being Castlelevington, the Tees and Corbridge. And Roseberry Topping or Manaw Gododd is the spiritual centre of his heartland. He fought battles at all these places and the Britons under his command pushed back the Picts and other attackers. What we cannot say is whether Arthur existed himself or whether this is just symbolic of a people and a geography.

As a parting question – are there other word puzzles hidden in Nennius’ text?

Indeed, as I think on it, I will reread Nennius. Thomas wrote that the Historia Brittonum was written after Bede’s The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and that the compiler had read Bede, and in a footnote, Thomas explains that ‘the historian David Dumville has pointed out the Historia Brittonum may have been carefully constructed to serve quite specific ends.’ If as I have proposed it includes hints as to the unwritten history of Rheged,I wonder whether it should be reappraised and that it was written specifically to be a counterargument to Bede’s history to balance Bede’s bias against Britons and towards the English.

Its use may be exactly what it calls itself, a history of the Britons, so where the compiler differs from Bede he is recording a different standpoint or knowledge that Bede has ignored or has come at it from a different angle, but also where he does not critique Bede maybe he is more accepting of Bede’s version. In the end, I will reread Nennius and ask myself if and why his set of notes differs or agrees with Bede, even if (or maybe especially if) those elements were fabricated!

Update (17/3/2023): I have not amended the whole of the above. However, I think Arthur is Rheged because taking my take that Nennius has made a puzzle and so the section on Arthur's Battles is a play on words above: Arthur is 'Ar Dwr' which means 'on the water' and links to 'Er Echwydd' which also means 'on the freshwater'. Tada! And so my suggestion in the second blog that it was Enlid was utter garbage.

References

John Morris (1980) ‘Nennius: British History and The Welsh Annals’ Phillimore, London and Chester.

Chantry Lewis (n.d.) ‘Early Latin Versions of the Legend of King Arthur’ British Library, London.

Images

Corbridge, Roger Coulam/Alamy Stock Photo (undated), Purchased and downloaded from Alamy with website licence (21/2/2023).

Roseberry Topping, Mark Sunderland Photography/Alamy Stock Photo (2009), Purchased and downloaded from Alamy with website licence (21/2/2023).

York, Robert Lazenby/Alamy Stock Photo (2016), Purchased and downloaded from Alamy with website licence (21/2/2023).