23 February 2023

The Lordship Of Elmet In West Yorkshire

Ted Hughes writes of Elmet as a post-industrial, West Yorkshire landscape, but in the sixth century Elmet was a small, British region allied to Rheged and fighting the invading Anglo-Saxons. Here we bring back some of that glory.

To the west of Rheged (North Yorkshire-Wensleydale), there lies the small land of Elmet (West Yorkshire), which the tribal hidage had down for a mere 600 hides or households, and written about by Ted Hughes. This is another hazy and difficult to fully pin down place from the sixth and seventh centuries.

It seems to have stretched from the Aire-Wharfe region to the Pennines in a rough southwesterly direction and down to the moors that mark the start of Lindsey-Lincolnshire. The border with Rheged seems fluid for two reasons: (i) at some point Urien is praised for taking Aeron, i.e., Airedale; (ii) places like Barwick-in-Elmet and Sherburn-in-Elmet that lie between the Wharfe and Aire seem to be making the point that they are in border country and where their loyalties lie, or at least lay at a point in time, but which is suggestive of disputed edgeland.

In Taliesin, poems 11 and 12 are praise poems to Gwallawg, lord of Elmet, who like Urien is a fifth-generation descendant of the semi-mythical Coel Hen. So far, I have set these poems aside as they differ from those of Urien, but, also, I do not know West Yorkshire so intimately. They are normally seen as showing Elmet as enemies of Rheged even though both are regions of the Britons. I am not so sure that they were enemies, definitely neighbours with their own borders, but I don’t see that they would not have marched alongside each other against a common foe.

Indeed, at least one of the soldiers who fought and lost at the Battle of Catraeth may have been from Elmet. Madog Elfed may be Madog of Elmet, so

'No grim ghost, his men defended,

lethal soldier, Madog [Elmet].'

In ‘In the king of Heaven’s Name, They Remember’ (poem 11), there are clues to the landscape and evidence that Gwallawg may have fought with Rheged. The space that is being described is very clearly Elmet and Gwallawg is named as the law-giver of Elmet, the lord of his small land.

The line, ‘o berth Maw ac eidin’, is translated as ‘Of events from Maw Edge and Eiddin’ which Lewis and Williams suggest is Edinburgh, so Elmet is fighting against the Scottish Gododdin. Because I locate Goddeu in Teesside rather than Scotland, I think the translation may be better seen as either a miscopying of Manaw Gododdin or be meant to say ‘Manaw Gododdin and Eidyn’, so we have something along the lines of (in prose) ‘they recount lengthy tales of Eden and Mount Ododdin’ or just ‘lengthy tales of Gododdin’. To the end of the poem, there are lines about being praised in ‘Prydein’ and ‘Eidin’ which I take to mean praised by the Britons and in Eidin, so in Rheged and Gododdin.

Gwallawg is active in Airedale so we have:

‘War’s armies shaking Aeron,

War, out of wanting the highlands and Aeron,

Bringing sorrow to sons.'

This sounds like fighting in the Pennines (the highlands) and around the Aire, i.e., Airedale. This is very definitely the land of Elmet. He is not fighting against Urien but defending his land from the Anglo-Saxons who are encroaching on his territory from the east.

Later, Gwallawg is again praised for fighting the Anglo-Saxons. He fights against them in York and Bernicia, so ‘Ebroc’ and ‘Bretrwyn’, or ‘Bretrwyn’ may just mean the hills because it could be hill, mount or promontory. This mind map is repeated at the end of the poem, where the poet mentions fighting in ‘Gafran’ and ‘Breicheinwac’, where the latter is Bernicia again; I have no idea about Gafran, though. Williams and Lewis-Williams have ‘Ybrot’ as ‘Ebroc’ or York and Bretrwyn as Brechin in Ayrshire.

Then, there is praise made for battles against the Anglo-Saxons ‘Lloygyr’ in Wensleydale ‘Gwensteri’. My discussion of Wensleydale covers the vale and the battle of Catraeth, so we are back in this Rheged landscape again.

There is, also, mention of ‘Pen Coet’, which may be the same as Gweith Pencoet, the battle of Pencoed, in the ‘Cadwallon’ poem. It may be the same wood that is mentioned in the next poem as ‘Penprys’. Woods were borders and barriers. Bede talks about silva Elmete and seemingly place names that mention trees and clearings of trees are common in Old English places to the south and west of Leeds, according to Thomas Williams in his book 'Lost Realms'. I am going to propose that Pencoed is to the southwest of Leeds and marks the edge of Elmet, beginning as you come over the Pennines. It would be very logical for the people of Gwynedd to talk of fighting here if they were trying to advance on Rheged from their base in the west, i.e. as in the poem ‘Rheged, Arise, its Lords are its Glory’.

There are two other pieces of natural landscape where I differ in my interpretations to those of Lewis-Williams, being ‘kat ycoit beit boet’ and ‘kat yn ros terra’. The first is translated as ‘Boar Woods’ which I imagine as being an allusion to woods near to York or maybe it is Pencoed again; I do not think it is Beith in Ayrshire as I don’t locate Aeron in Scotland but in Yorkshire.

The line about ‘war on Snow Moor at dawn’ does not feel right, because the poet is very specifically talking about a type of land which is characteristic of South Wales. He is either using that as a description of a type of moorland that his audience would immediately know or maybe it does relate to the same landscape in Yorkshire. ‘Ros terra’ means rhôs moorland which is characterised by big tussocks of Molinia grass and wet ground and we’ve got loads of it in our wood, Coed Olaf. It’s almost impossible to walk through, so I envisage it as a battle on flat ground with an edge created by rhôs moorland, i.e., the poet’s ‘ros terra’. This rough, tussocky moor could be in Wensleydale or to the south of Elmet where the landscape becomes fenlike towards the Don or east of Ferrybridge where the Aire merges into the Humber. I reckon it’s the latter because we seem to be fighting near York, perhaps pushing back the advancing Anglo-Saxons as they come up the Humber from their base in Holderness.

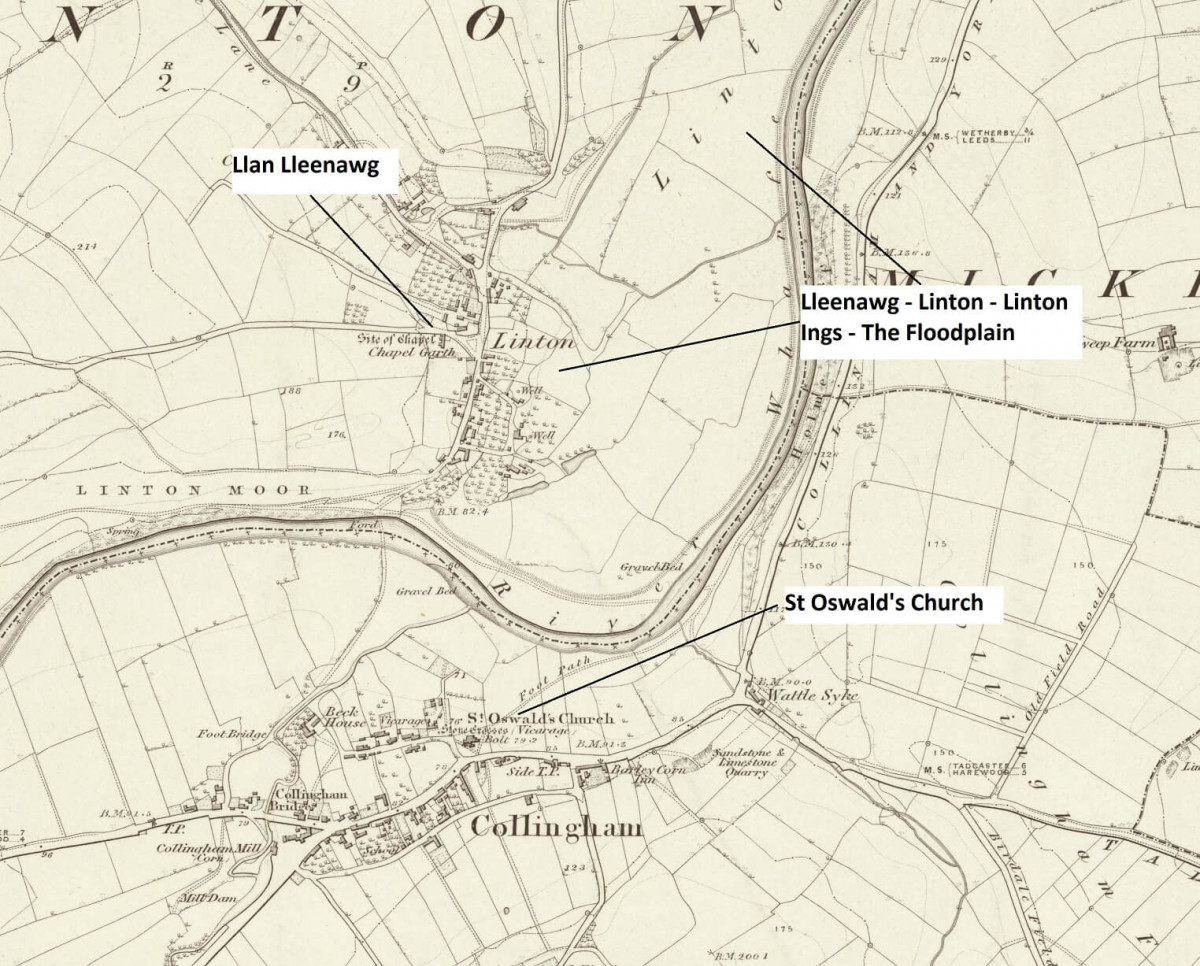

There are questions, always still loose ends. I do not know where Llan Llenawg is, which seems to have been an important Christian site for Elmet. It cannot be Anglesey, though. Likewise, Gafran does not click quite yet, but perhaps it is Garforth which is close to the edge of Elmet, near Leeds (Loidis) and Sherburn-in-Elmet, and so its derivation may be Brittonic and not Old English as normally suggested.

That having been said, I am going to propose a place for Llan Llenawg, why not, I am in too deep? I read the place as llan lleenawg, meaning 'church of the place of lleen' or 'church near the floodplain', where līn is a 'flood, deluge, stream, current.' There is a place on the edge of Elmet-West Yorkshire called 'Linton' which likewise means 'the place of lin' which is usually translated as 'the place or farm where flax is grown'. I think this is wrong and it is a transferral from Brittonic into Old English of the old British name for the place, i.e., lin. Now, Linton is located right beside Linton Ings, i.e., a local floodplain of the Wharfe, and there is evidence that this site was occupied in prehistoric times, Roman times and crops marks date from c. 800. There was also an old church that has disappeared. I am going to say that Llan Lleenawg is the church at Linton, which describes the edge of Elmet. Intriguingly, Collingham has a church dedicated to St Oswald which may either mean it was built to counter the British church at Linton or was a rededication of the church we are looking for - its renaming would have been a very political act, i.e., Englishing a British religious site.

Caer Glud and Caer Caradawg are likely the places mentioned as ‘Alt Clud’ or Dumbarton and Caer Caradoc in Shropshire. I like to imagine that the Britons used Caer Caradoc as their base to attack back into the lost lands of the Old North, even if it is a bit too far south in reality.

So, overall, I think that the poems praising Gwallawg of Elmet are complementary to those for Urien, and that they not should be seen as being against Urien. That having been said, Elmet was clearly an independent place, with its own geography and history.

Indeed, the poems to Gwallawg describe a land that goes from the Wharfe in the northeast around Linton (its normal edge with Rheged) to Elmet wood and the Pennines in the south west, then to the moors in the south on the border with Lindsey, while to the east there were the encroaching Anglo-Saxons with a base at York, maybe.

References

Gwyneth Lewis, Rowan Williams (2019) ‘The Book of Taliesin: Poems of Warfare and Praise in an Enchanted Britain’, Penguin, London.

Gillian Clarke (2021) ‘The Gododdin: Lament for the Fallen’, Faber & Faber, London.

Sir Ifor Williams, translated by J. E. Caerwyn Williams (1975) ‘The Poems of Taliesin’ The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin.

Thomas Williams (2022) 'Lost Realms', William Collins, London.